Illegal employment agency fees can run as high as three years worth of migrant workers’ salaries. These fees have been affecting them tremendously, but they do not know where it is going.

To better provide for his family, Mr Hasan Md Rakibul took a bank loan, sold off one of the two houses his family owned, borrowed money from various family members, and his mother even had to sell what little gold she had, just to pay an employment agent a steep recruitment fee of S$15,000 to work in Singapore.

It took the 29-year-old insulation technician four years to pay off his debt, spending only S$7 per day just to send money back home to his loved ones.

Mr Rakibul, who is reaching the end of his contract next year, said: “I always think this way, ‘How can I finish my loan?’ Always in my mind is this deal only.”

And that is just the tip of the iceberg for many migrant workers in Singapore.

Most work-permit and S-pass holders in the Construction, Marine, and Processing (CMP) sectors have been subjected to exorbitant agency fees in their home countries to secure a job in Singapore, but many have no idea where this high amount is going. Regardless, the lack of transparency has taken its toll on their overall wellbeings — mental, physical, and financial.

SO, WHERE DOES THE MONEY GO?

According to the Institute for Human Rights and Business, the recruitment fees that agencies collect are supposed to cover expenses such as transportation, accommodation, medical examinations, and work permit applications.

But Mr Mynul Islam, a crane operator who actively participates in Tzu Chi Humanistic Youth Centre’s activities, shared that from his experience, there were no official documents stating explicitly where the fees went.

“They have no any proper formal writing. Or any papers also don’t have. So they just writing on like any pad. ‘Okay this money you already pay us,’” shared the worker who has been in Singapore for over 10 years.

He discovered this during a conversation with an employment agent back in Bangladesh after “graduating from the recruitment training centre” he was in.

The typical process of hiring prospective CMP workers involves entering a recruitment training centre located in their country, where they would receive some training to prepare them for their future job in Singapore.

Subsequently, upon receiving a certificate to acknowledge their abilities, migrant workers will connect themselves with employment agents either from Singapore, or through recommendations from friends and family at home, who will charge a fee for their services.

The Ministry of Manpower (MOM) states in its guidelines that Singapore employment agencies are only allowed to collect one month of a worker’s fixed-monthly salary for each year of service, capped at two month’s salary.

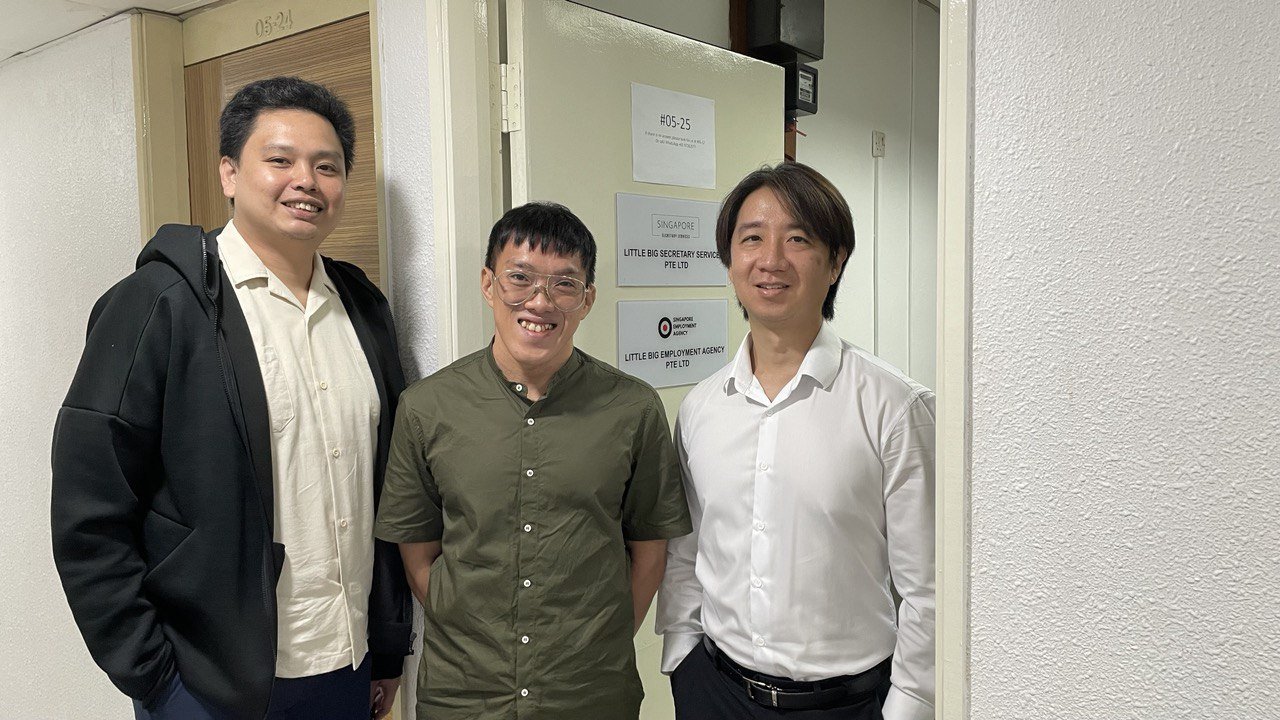

However, this may not be the case for employment agencies outside of Singapore, and Little Big Employment Agency’s Mr Kevin Yeo, 41, says that local authorities do not have jurisdiction over illegal transactions that happen offshore.

“From my understanding, [employment agency services] is all on a referral basis,” he shared. “[Authorities] cannot control anything that happens beyond [our shores].”

This makes it much harder for migrant workers to pinpoint how they are being exploited, and has its own reverberations on them.

MIGRANT WORKER WOES

The total cost of Mr Rakibul’s loan was S$15,000. With an average price of S$5 per cup of bubble tea, this amount would allow one to purchase 3000 cups.

This shows the scale of the loans that migrant workers are willing to undertake just to get into Singapore. Case Officer Mr Mohamed Alfiyan, 33, from migrant-rights group Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2) expresses one possible reason why migrant workers resort to illegal agents: desperation.

This desperation to find a job to support their family leads to much sacrifice in order to pay exorbitant fees to agents. The debt incurred afterwards, however, puts a lot of pressure on them, resulting in a domino effect.

“After paying money, they are financially in debt. Because of the low salary, they work overtime, then they lack rest, which affects them physically,” shares Mr Alfiyan.

He added: “If [they] lack rest, [they] won’t be able to concentrate at work and may get injured. When injured, a migrant worker may not be able to find a proper job.”

This puts migrant workers in a more precarious position than before. Furthermore, if a migrant worker is forced to return home, be it from injury or otherwise, they will have to go through the same expensive process.

For some migrant workers, this means that it’s more than just a domino effect — it’s a vicious domino cycle. Mr Omar Sakib, 35, a safety co-ordinator that participated in IAmInvisible Do You See Me Story Exhibition 2022, shared his experience of being deported twice due to irresponsible employers, leading him to repeat the whole process of getting a job in Singapore.

Hence, accumulating more employment agency fees and the emotional toll that comes with it. Another side of the emotional toll that migrant workers face is their yearning for home during their contract. Mr Mynul shared that he felt trapped in Singapore as he was unable to purchase a plane ticket back home to Bangladesh. As a result, he missed watching his daughter grow up.

“I have a daughter. I never see her. I never saw her grow up so this kind of things make us emotional,” said Mr Mynul as he teared slightly. “So, this is like timing, you know? [We don’t just] think about the money, we think about the [time we lost].”

Despite the known issues surrounding the high fees, why does this scenario keep occurring time after time again?

ROOT CAUSES

Aside from feelings of desperation, one of the factors of this occurrence is the lack of transparency. There is a lack of a medium to serve as a middleman, allowing these illegal employment agencies to swoop in.

Mr David Kalimuthu, 39, a Case Officer at TWC2, shared that while Singaporeans have the advantage of job portals like LinkedIn, “no such platform exists” for work permit-level jobs, so migrant workers are forced to go to employment agencies. This is corroborated by the observations from Mr Mynul and Mr Rakibul.

Mr Mynul shared that it was difficult for prospective CMP workers to look for job positions in Singapore online. It was easier to receive gratification through referrals from friends; the closest thing to an online job posting would be websites identifying companies as training centres.

The training centres and employment agents also advertise themselves on social media and WhatsApp message blasts, pushing the middlemen narrative farther.

“They just find the people then just go to the training centre. It’s like that. Don’t have any proper way how they can come from Bangladesh to Singapore [via online job postings],” Mr Mynul emphasised. “It’s no have any proper way.”

Mr Rakibul shared that they are unable to secure a job or even come to Singapore until they find an agent.

“Whenever we want to go [to Singapore], we must find agent. So for us migrant workers, we need that link [as a direct point-of-contact] to Singapore,” he elaborated.

However, it is not just the lack of opacity in the hiring process, but human behaviour as well. Little Big Employment Agency’s Mr Daryl Lum, 42, added that another possible cause for the high employment fees is greed.

“Illegal things only happen when there’s money to be made,” said Mr Lum. “So why does it exist? Human nature.”

ACTIONS TO TAKE

In order to combat these illegal employment agency fees, MOM has produced guides for migrant workers to educate them about their rights. It states the specific fees that agencies would collect, and if the CMP firm they are working at terminates their contract, the fees are liable for refund.

TWC2 has also been advising migrant workers via casework, and dissemination of relevant information to further educate and encourage other migrant workers to approach credible and legal agencies in Singapore.

They elaborated that it is difficult for them to reach out to first-time workers, so they try to “warn workers about” these illegal employment agencies through their Facebook page.

“So those who are following our Facebook, hopefully they will be able to share this information back with their friends in their home country, so that will maybe, possibly by word-of-mouth, it can help to solve some issues,” Mr Kalimuthu added.

Moving forward, they are advocating for job portals to be set up for finding work permit-level jobs. As mentioned by Mr Kalimuthu, migrant workers lack the luxury of job portals. Mr Alfiyan shared that the goal is to create a more straightforward arrangement for them to look for jobs in Singapore.

“Because if you are to cut the middlemen, then it’s much more, I think, safer and easier [for the migrant workers],” shared Mr Alfiyan.

Mr Mynul says that if there were to not be a job portal, the Government would at least make changes to the system to increase transparency.

“I hope my future brothers who really want to come to Singapore [can go through a better system],” said Mr Mynul.

This piece was produced as part of the Diploma in Mass Communication of the Republic Polytechnic in collaboration with the Tzu Chi Humanistic Youth Centre.

Team: AISHA HASSAN, FELICITY OH, LEE REN QUAN, NURUL INSYIRAH BTE MOHD SHUKOR, SYARIFAH SALMAH NADHIRAH BINTE SYED NASIR ALJOFRI