Despite being a country that prides itself on racial and religious equality, how Singaporeans view migrant workers has been questioned for not giving them enough respect. As more migrant workers come to our shores, how can we change our perceptions of them?

Growing up in Singapore, one is more than likely to have seen migrant workers in the community or in their daily lives. Whether it’s the humble construction worker helping us build a new facility in our estate or the domestic worker taking care of our families, in some ways, they have become a part of our communities.

According to the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) foreign workforce numbers, there are around 943,400 work permit pass migrant workers in Singapore in 2022. The Government has repeatedly stressed that migrant workers are necessary due to our ageing workforce and their importance to Singapore’s economic success. This is a sentiment echoed by many Singaporeans, who also view migrant workers as the ones doing jobs that they are not willing to do. In a survey where we polled 91 respondents, almost 98.9% of respondents believed that migrant workers are important to Singapore’s economy.

However, that is the extent to which many Singaporeans view migrant workers. With the number of migrant workers set to increase in coming years, it is undeniable that the presence of migrant workers in Singapore will only continue to rise. Thus, is it time for us Singaporeans to rethink and ultimately, change the way we treat migrant workers?

Why this is a problem

A study from the International Labour Organization (ILO) mentioned how “The equality of treatment is not the norm in terms of public attitudes towards migrant workers. Based on their research, 75% of respondents agreed that migrant workers should not have any rights at work if in irregular status, and 60% agreed that if migrant workers are exploited, they have themselves to blame.

Chua Ning Pei, the founder of IAMinVISIBLE, a Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) dedicated to migrant workers said, “I think it’s all about the mindset because Singapore is multicultural and it’s one of the first-world countries in Asia where everything is the best.” Despite this, not many Singaporeans are exposed to workers from different countries, but many hold prejudices based on their occupation, hence they sound indifferent, she added.

However, this unfavourable perception of migrant workers is not a new occurrence. In 2008, 1,400 out of 7,000 residents in Serangoon Gardens petitioned against building housing for foreign workers next to their homes. While the debate was initially centered on overcrowding, congestion, and traffic management, it quickly became classist, with many onlookers noting how residents wanted to reject the presence of “alien” foreign workers in their estate.

In 2013, in one of Singapore’s largest anti-government rallies, more than 1,000 people gathered at Speaker’s Corner to protest against the surging number of foreign workers.

But it was only when COVID-19 struck that Singaporeans got to see what was happening on the other side.

MOM reported that the suicide rate amongst Work Permit Holders compared to Singaporeans was higher in 2020, a reversal from the trend from 2016 to 2020. Additionally, research done by Assistant Professor Jean Liu and her team of researchers found that COVID-19 restrictions had greatly affected the mental health of migrant workers, and had increased the symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress.

Even as restrictions were being lifted for Singaporeans, thousands of construction workers were still confined to their dormitories, only receiving limited outside contact. This brought the issue of the mental health of migrant workers into the spotlight.

Hardships of migrant workers in Singapore

Julie Ann Tabigne, a mother of a 10-year-old boy, is a domestic helper from The Philippines. When she first started working in Singapore 10 years ago, she recalls how her first employer prohibited her from using her phone until she finished all her tasks, usually ending around 11 pm at the earliest. However, by the time she was able to call her family back home, they were already asleep. That was until she received news that her mother was in hospital.

Desperate to know about her mother’s condition, Julie used her phone during her lunchtime. But when her employer became furious upon finding out that Julie was using her phone, she snapped, “This is the only way I can contact my family and my mother is in the hospital. So do you want me to get the news that my mother’s already dead? Your family is here with you, but my family is away from me.”

Similar experiences are also felt by our fellow construction workers. Omar Sakib, a Bangladeshi national who has been working in Singapore for 13 years as a safety coordinator, vividly recounts how some Singaporeans try to stay away from him despite living alongside them for many years. “I can see two to three Singaporeans standing close to the door on the MRT, and when I enter, they move aside, maybe to give me space, but I can feel that the way they stand aside, they don’t like to stand beside us. Even on the streets when we gather, I can tell that the locals don’t want us to be there,” he says.

After the circuit breaker was announced, Omar became involved in many community collaborations and worked with various NGOs and local communities. Through his volunteer work, including a collaboration with NUS students, he found out that youths assume that migrant workers live in a certain way when in reality, they don’t understand the full picture.

Are youths at fault?

Ning Pei also mentioned that the youth are generally apathetic. “They’re misinformed and they don’t care. There isn’t any intentional and sustainable opportunity to bring these two groups together to understand and engage with each other,” she added.

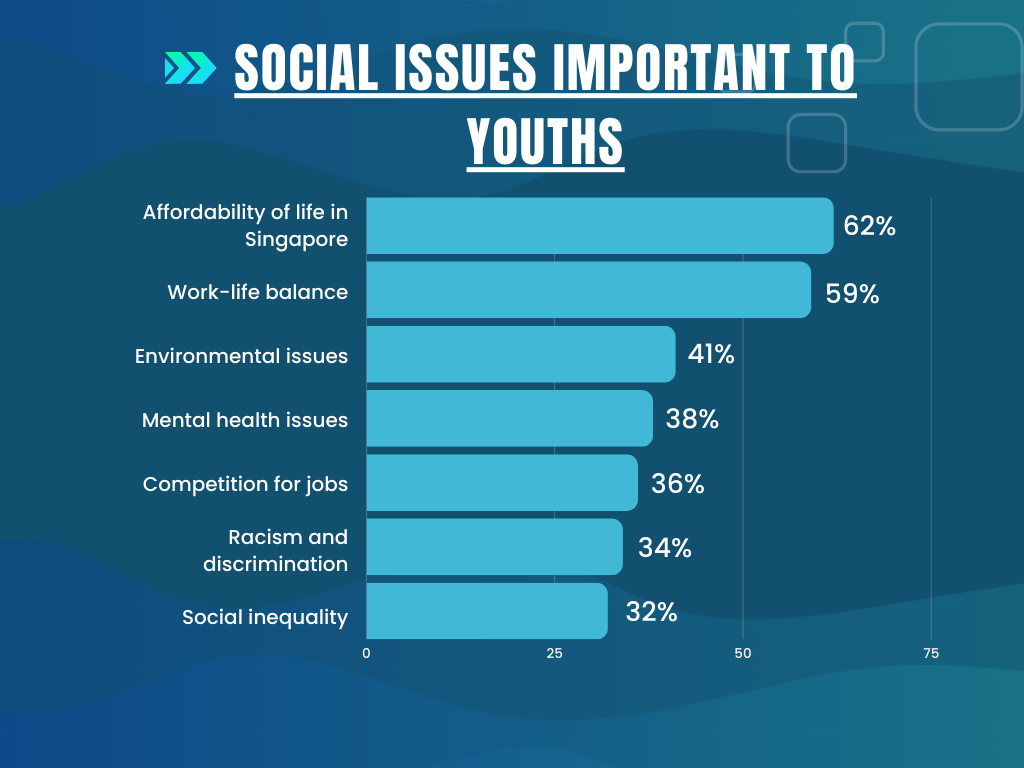

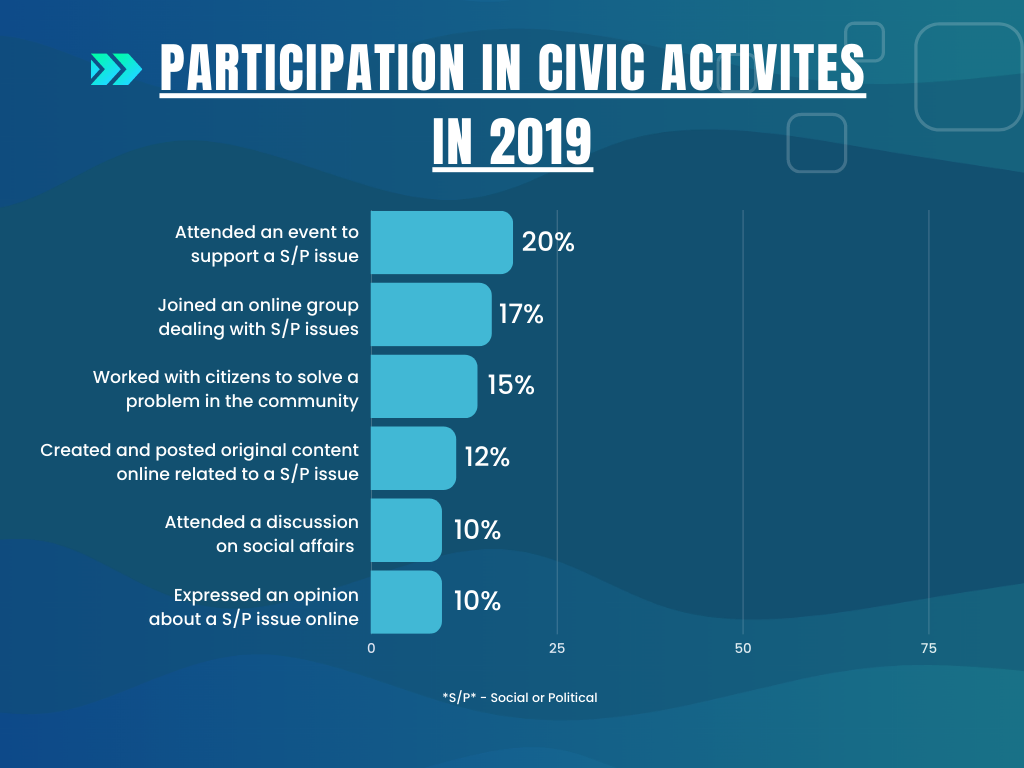

A 2019 National Youth Survey surveyed 3,392 respondents and found that youths are much more concerned about other social issues compared to the issues of migrant workers. Volunteerism and participation in civic activities among youths have also decreased.

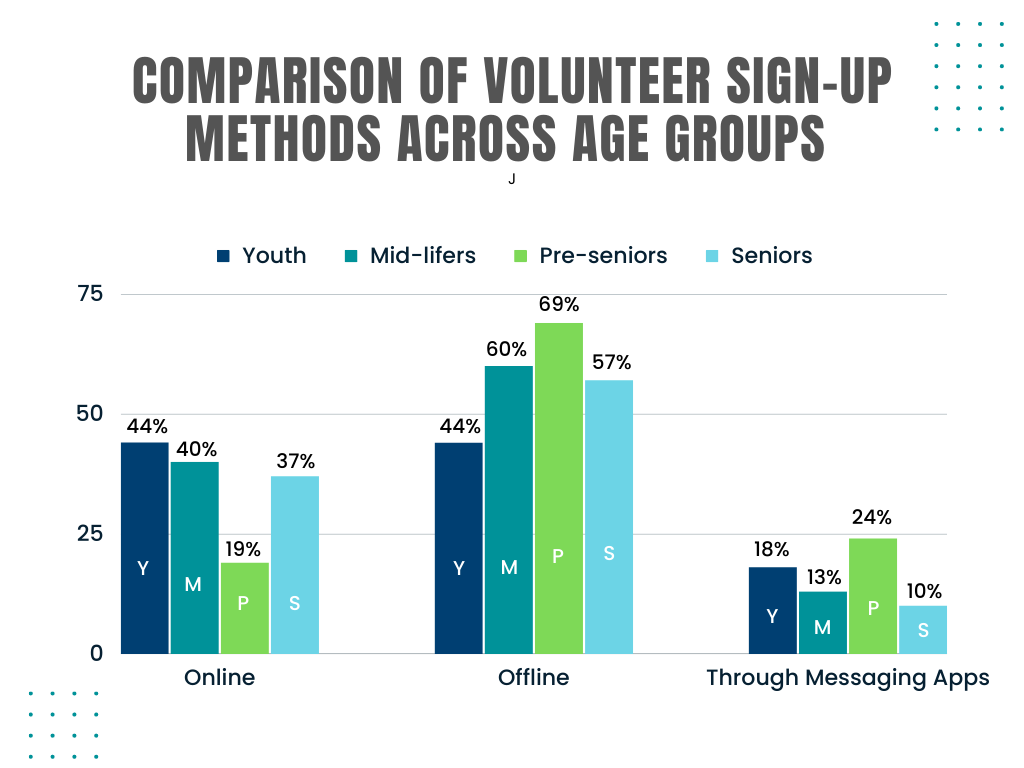

Additionally, the National Volunteer and Philanthropy Centre (NVPC) surveyed 2,004 respondents as part of the 2021 Individual Giving Study and found that Singaporean youths do not volunteer as often compared to other age groups.

This has led many to agree that Singaporean youths are apathetic towards migrant worker issues, not only due to their lack of involvement, but also through their personal observations. “Whenever people walk past a migrant worker, they usually treat them as an invisible object and just walk past them, even if they are in a difficult situation like having no shelter when it’s raining or sleeping under the HDB blocks,” said Jedd Kua, a 15-year-old secondary school student.

Although Jedd agrees that youth apathy is present, he believes that it is not the main cause of the division between the 2 communities. Rather, it is due to the differences in living standards, stating, “their salary is generally lower than the average Singaporean and they are unable to get the benefits that most Singaporeans get. They also live far away from Singaporeans, hence have little to no chance of integrating with locals.”

Others, like Jackson Yeo, a 20-year-old Republic Polytechnic student, attribute this behaviour to the busy lifestyle of many Singaporeans, saying “I feel that as the majority of Singaporean youths are busy with their daily lives. Thus, they are subconsciously being apathetic towards them while some of them truly show no interest as it does not involve them.”

However, not all youths agree with this sentiment. Alvona Tan Si Qi, a 19-year-old Nanyang Polytechnic student thinks that youths do care about migrant workers as she often sees people posting about helping migrant workers on social media. However, she admits that within her group of friends, they usually do not talk about migrant workers, which she also attributes to the busy Singaporean lifestyle. “We already have our stuff to do and we are busy in life already so we don’t usually care about what other people’s problem is unless it really concerns us. It’s you do you, I do me kind of thing,” she says.

Old attitudes die hard

However, many say the problem does not lie purely on the shoulders of youths. Some believe that cultural upbringing plays a part in youths developing a set of preconceived notions about migrant workers from a young age that leads them to be subconsciously apathetic to migrant workers when they are older.

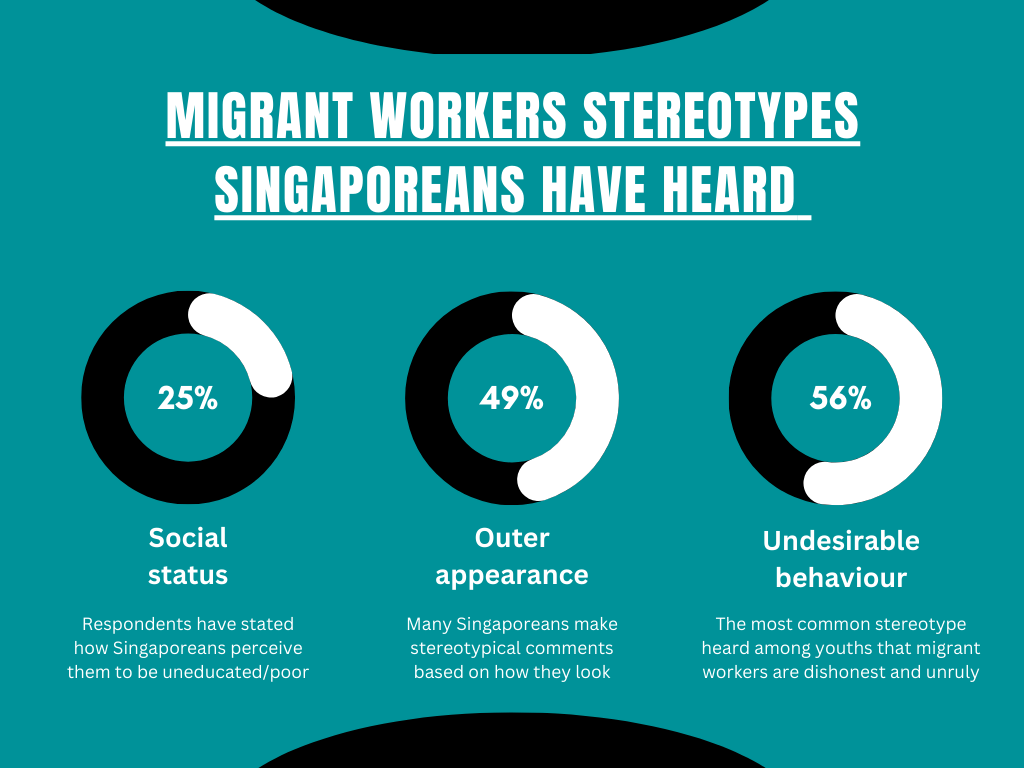

Based on our survey responses, 95% of respondents have been exposed to at least 1 type of stereotype of migrant workers. The following figure shows the percentage of respondents that were exposed to the various stereotypes.

These attitudes persist through many generations and Ning Pei recalls how she grew up with such negative sentiments from her elders and how they hinder one’s understanding of the migrant community.

“There is a common stereotype that migrant workers are poorly educated or are untalented when in actual fact, many of them are educated with some even having a degree and various artistic talents such as writing poetry and dancing,” she says.

Additionally, it can be hard for these attitudes to change amongst the youth because as Alvona Tan recalled, there were hardly any opportunities to interact with migrant workers, “In secondary school for projects such as Values-In-Action (VIA), it’s mostly with elderly or kids but not with foreign workers because they were working. Hence they have no time to interact with youths either, ” she added.

Change is coming

However, all hope is not lost. There are youths who have taken the first step to understand migrant workers to help them better.

Wei En, 18, has been volunteering for about 9 months for Raining raincoats, an NGO that aims to bridge migrant workers and Singaporeans. Before she volunteered, she had preconceived notions about migrant workers due to stereotypes that are often perpetuated by the media and society. But through her interactions with the migrant community, she realised that the stereotypes were inaccurate and started to develop a deeper appreciation for them and their contributions to Singapore.

Her parents were also a huge pillar of support for her to continue volunteering with migrant workers, and she cites how she was inspired by her mother’s regular volunteering with her church distributing care packs and food to continue volunteering.

“I wanted to do something that could make a difference, even if it was just making one person a little happier.”

Other NGOs are also playing their part to create a positive social impact. For example, the Tzu Chi Humanistic Youth Centre launched the Mental Health Awareness and Wellbeing festival in 2021 and 2022 to encourage positive sentiments about migrants, and build empathy and understanding amongst the youth as a way to build bridges between locals and migrants.

The Centre also launched several Stay home quilt participatory arts projects in July 2020, where youth volunteers and migrant workers sew together using recycled cloth in two to three engagements, as a way to encourage sharing between the two groups.

Through these efforts, there is hope that Singapore society will change the way it treats migrant workers. “Maybe my job is dirty. But as a person, I’m not. I hope everyone treats our construction workers, migrant brothers, and sisters as a friend, and that we won’t have this hesitation to say hi and greet each other on the street,” Omar says.

This piece was produced as part of the Diploma in Mass Communication of the Republic Polytechnic in collaboration with the Tzu Chi Humanistic Youth Centre.

Team: LOKE JON TOW; MICHELLE LAI KEXIN; TAY ZENNETH; TAY JING NING, JERLYNN; PHUA JIAN LE